This is the first of a series of in-depth interviews with our esteemed legal leaders; our legal luminaries. Sir Peter Blanchard looks back over his life in the law, speaking candidly about its high and low points, offering sage survival advice for younger lawyers and discusses what he thinks are the most important legal issues right now. The result is a fascinating insight covering the how, when, what, where, who and why of a stellar legal career.

This is the first of a series of in-depth interviews with our esteemed legal leaders; our legal luminaries. Sir Peter Blanchard looks back over his life in the law, speaking candidly about its high and low points, offering sage survival advice for younger lawyers and discusses what he thinks are the most important legal issues right now. The result is a fascinating insight covering the how, when, what, where, who and why of a stellar legal career.

About The Legal Luminaries Project

In any sphere of human endeavour there are people whose sustained, consistent, and informed contribution within their specialist field of knowledge forms the foundation for those following in their footsteps. They are luminaries. The debt we owe them is incalculable as it is their work literally lighting our way forward.

The Legal Luminaries Project acknowledges the legacies of our esteemed legal leaders and seeks to give an overview of, and insight into, their lives within their specialist fields; to shine a light on the core values, thinking and events underpinning their successes.

Methodology

The information in each profile was collected over a series of interviews. The subjects covered and/or the questions asked appear ahead of their answers. Each of those is prefaced in bold with the interviewee’s name: e.g. Sir Peter.

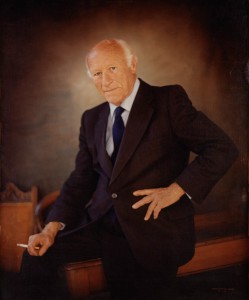

Sir Peter Blanchard

A brief background

Sir Peter Blanchard is one of New Zealand’s outstanding jurists. He attended the University of Auckland Law School, was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship and then a Frank Knox Memorial Fellowship from Harvard Law School. He was a partner in the Auckland office of law firm Simpson Grierson and a director of several listed companies until his appointment to the High Court in 1992. He became a Judge of the Court of Appeal in 1996 and of the Supreme Court of New Zealand in 2004 where he sat until retiring in 2012. He was appointed a Privy Councillor in 1998 and is a former Law Commissioner.

Sir Peter Blanchard is one of New Zealand’s outstanding jurists. He attended the University of Auckland Law School, was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship and then a Frank Knox Memorial Fellowship from Harvard Law School. He was a partner in the Auckland office of law firm Simpson Grierson and a director of several listed companies until his appointment to the High Court in 1992. He became a Judge of the Court of Appeal in 1996 and of the Supreme Court of New Zealand in 2004 where he sat until retiring in 2012. He was appointed a Privy Councillor in 1998 and is a former Law Commissioner.

Currently Sir Peter is an Acting Judge of the Supreme Court of NZ, a Court of Appeal Judge of Tonga, Samoa and Kiribati and the Consulting Editor in Chief of A –Z of New Zealand Law.

Contribution to law

– If you viewed your career in the law as an outsider, what would you say your main contribution or legacy was?

Sir Peter:

“Perhaps reform of the Property Law Act which was the subject of a Law Commission report in 1994. This was completed over four years of work that I led part time during which I was appointed to the Bench.

Much of the 1952 Act was impenetrable having been unaltered since (in some cases) 1842. It needed a complete vocabulary and meaning overhaul. The original context and environment in which it was drawn up no longer existed and on top of that, changes and additions to the Act over the years made it increasingly difficult to comprehend and apply.

The resultant Act, although longer, was modernized, clearer and more comprehensive. It finally became law in 2007.

Property law is decidedly “unsexy” for politicians

The reasons for the years of pigeon holing and delay were mainly due to its lack of public profile. Also the overhaul and review of the Act was undertaken by the Commission of its own volition rather than as a response to a governmental request. It was not on the political radar at the time, probably because it was decidedly “unsexy” and therefore something that did not attract their attention.

It wasn’t until a complaint about lack of progress was made to then Prime Minister Helen Clark that any action was taken.

Inevitably because of the lengthy delay between the completion of work and its impending implementation the entire Act needed yet another revision – mostly harmonizing with what Parliament had done in the meantime.

Sir Geoffrey Palmer, who was the President of the NZ Law Commission at the time, persuaded the Government to engage in a programme of reviewing old Law Commission reports with a view to actioning them. He asked me to oversee the updating of the PLA. That took nearly a year to complete. The revised Act finally came into force in 2007.

(On the role of the Law Commission and its importance)

What happened is yet another consequence of a decision to ignore or sideline the Law Commission’s work. Unimplemented reports cause significant problems further down the track. The remit of the Law Commission, declared in its founding legislation, is to monitor and critically analyze the law with a view to identifying and proposing solutions to its possible shortcomings. Reports like the Property Law Act or the still unimplemented Land Transfer Act report, were never generated frivolously but because they are needed.

(Delay equals expensive, embarrassing, future muddles)

The process of having to persuade politicians that proposed reforms are worthy of their time and effort is a major undertaking, despite the fact that they would, sometimes, if actioned, avoid very public embarrassment from not taking them on board. A high profile and highly contentious example of that is what happened as a result of the 2007 Urewera police raids on what was assumed were para-military training camps. Arrests were made and charges laid.

A Bill based on a Law Commission Report on Search and Surveillance was at the time languishing in Parliament. The police were therefore acting in a legal vacuum.

Many of the initial charges laid by the police had to be dropped because the evidence was ruled inadmissible. Recently the Crown formally apologized for its role in the fiasco. Some of this could have been avoided if the Law Commission’s report had been actioned earlier. Decisions to overhaul law should not be forced by public outcry or made in the immediacy of the moment.”

Early years

Sir Peter:

“I grew up in Auckland – an only child of a widowed mother.

My father was lawyer. He was killed in action in World War Two when I was ten months old. I wasn’t at all pressured by my mother to follow in his footsteps. It was something I chose for myself.

I grew up knowing I had a place, a job to go to, when I left school. Max Grierson, one of the founding fathers of Simpson Grierson had been a friend of my father. He was a trustee of my father’s estate. Max made a promise to my mother when I was a child that I would always have a job in his firm if I wanted one. I did, and joined the firm in 1962.

In those days the firm was very small – around five partners. It was also the days of very limited equipment. There were no photocopiers or any form of electronic wizardry. We had typists and everything was handled in hard copy – real paper, in real files. I was the law clerk; the gofer. I was sent to take to, and fetch documents from, the stamp duty office and the transfer office where they were stamped and registered. As was typical in those days I attended law school part time; alongside my “go-fer” work.

I stayed with the firm thirty years.”

Values

– What values have you held strong throughout your career?

Sir Peter:

“The values I hold dear are ones that have served me all my life: honesty, loyalty and hard work. I don’t believe you can be a good lawyer without them. I think they need to be deeply engrained – etched into the fibre of your being – along with a healthy respect for the legal system itself.

I also think these values are universal. If you care about yourself, the people you work with, and those you serve, you’ll see those values mirrored wherever you are. Like attracts like and becomes mutually reinforcing.”

– Who has inspired or continues to inspire you?

Sir Peter:

Sir Peter:

“Max Grierson is an enduring role model for me. He continued working until his death in 1993 aged 93.

Max was the epitome of what I call an “instinctive lawyer”. Because of the combination of his innate sense of fairness, straightforward approach, experience, and understanding of common law principles, his opinion was always valuable, and always welcome.

As he grew older my respect only increased, such was the insight he brought to the table. His practical clarity – the ability to see likely outcomes, was extraordinary.”

– What personality or character attributes are needed to become a good lawyer?

Sir Peter:

“In my opinion a good lawyer has in equal measure patience, honesty, loyalty and persistence. They are always prepared to work hard and of course experience also helps. It usually trumps superior intelligence.

…being seen to be clever, is not a sustainable career plan.

Merely being clever, and being seen to be clever, is not a sustainable career plan. Systematically accrued, applied experience and hard work is the foundation of a successful life in law.”

Memories

– When you look back what memories come to the fore?

Sir Peter:

“As a young person going to the United States to study at Harvard was a marvelous experience. It gave me the opportunity to measure myself against the best America and the rest of the world could produce. That was particularly exhilarating, as was joining the London firm Paisner & Co (now part of Berwin Leighton & Paisner) on leaving Harvard. I remember how, despite being a young and inexperienced negotiator, I was routinely thrown in the deep end like for instance being sent to Bermuda to deal with a multi-million dollar contract for hotel outfitting.”

– Is there are a particular memory you are most fond of?

Sir Peter:

“I remember the marvelously erudite and lengthy letters I received from Sir Alexander Turner. He was a great judge and a wonderful author who after retiring from the Court of Appeal became Butterworths of New Zealand Director and Editor in Chief. I got those letters because he oversaw the publication of my second book: “The Law of Company Receiverships in Australia and New Zealand”, and I still have them.”

– Is there a memory you are most proud of?

Sir Peter:

“One particular memory takes me back to 1992 and my first year on the High Court Bench. I had very little litigation experience coming from a commercial background and I had to learn very fast. Within a few months I was presiding over the trial of the high profile and extremely contentious leader of the CentrePoint Community, Bert Potter. I remember there were numerous technical difficulties over some of the rape and assault evidence and counsel and I had to work our way through them in the glare of considerable publicity. It wasn’t easy, but it was an extraordinary time early in a career on the bench.”

– What memories do you have of the process underpinning your choice to move into what became your specialist area?

Sir Peter:

“One of the best things you can do for yourself is to try to get to know your own strengths and weaknesses. Both shape who you become. I realized quite early on I was not a court room lawyer. I couldn’t think fast enough on my feet or retain, and accurately recall, detail without the luxury of time to think, to prepare. After several, of what I thought, were “appalling” personal performances in the Magistrate’s Court I let that facet of law work go and turned my focus to the areas I felt were my strengths.

There is nothing to be gained through trying to force yourself to become something you are not.”

– Do you remember a particular incident shaping how you developed in your chosen field?

Sir Peter:

Events provided opportunities I could never have foreseen.

“Several events, independent of each other, but directly affecting my career path occurred at a formative time when I was consolidating my future direction.

The first of these was a series of ongoing mergers. The firm I’d joined as a law clerk was small. In 1983 it became Simpson Grierson and with 40 partners was one of the largest in the country. The challenges of managing size required a different way of making partnership decisions.

The old model of management was replaced with an Executive Committee. I was on leave at the time this was being set up and in my absence I was appointed to the role of Chairman. That was a position I held for about 5 years, during which time we did a further large merger and moved premises.

As the firm became larger it made it possible for lawyers to specialize – to hone and develop skills in particular areas of law. My field of expertise had been initially conveyancing, and then commercial law. I was fortunate enough to have had several big clients put my way and to have achieved some successes on their behalf.

Another career highlight was appearing as one of the counsel for the Crown in the first of the major Waitangi Tribunal cases, the South Island Ngai Tahu claim. This was heard over two years, from 1988 to 1990, and involved me in extensive traveling all over the South Island as well as intense periods of preparation in the Crown Law Office in Wellington. I found it fascinating researching the history of significant land purchases between 1840 and 1860. It revealed a world I knew little about hitherto.

Events provided opportunities I could never have foreseen. The Leading Counsel for the Crown suffered a personal health crisis, developing a problem with his eyesight. So, instead of acting in a backroom role, I had to support Shonagh Kenderdine, later an Environment Court Judge, in a barristerial role in what was possibly the largest piece of litigation ever before a New Zealand tribunal.”

– What was the most difficult/challenging period of your career?

Sir Peter:

I would probably not have accepted the appointment had I known what was in store in my first twelve months: the Bert Potter trial and an equally complex gang rape trial in Rotorua.

“The most difficult period was when I was appointed to the High Court Bench. I had no litigation background, little knowledge of the rules of evidence or civil procedure. It was hardly an adequate background to deal with the criminal trials I found myself presiding over. This was potentially very scary, and not just for me! I would probably not have accepted the appointment had I known what was in store in my first twelve months: the Bert Potter trial and an equally complex gang rape trial in Rotorua.

However, I had accepted the appointment and was determined to succeed. Actually it was exhilarating, despite the sordid nature of the cases. I am indebted to the wisdom of Robert Smellie for the advice he gave me when I was considering whether to take the appointment. He pointed out that I did not have to know everything all at once. I could take things slowly and control the pace of the trial and I could get help from other judges. I took every opportunity to ask questions at morning and afternoon tea time. And counsel went out of their way to be helpful to a new judge, for which I was most grateful. That experience gave me confidence in myself and the judicial process.”

Legacy advice

– If you were able to give career or personal advice to the young you – what would it be?

Sir Peter:

“If I could whisper in the ear of the younger self I would reiterate what I’ve known to be true all my life.

I would remind myself of the values making my life meaningful: fairness and loyalty to my partners, clients and the legal system itself. I would say work hard, persevere and always try to produce work of the best quality you can manage.”

– What are your top 3 tips for young lawyers?

Sir Peter:

“Work out what your client needs, rather than what they want. There is a difference, although in the end you must follow your instructions.

…dismiss nit picking, or escalating minutiae to centre stage

Do not allow yourself to become distracted by collateral detail. Focus on the bigger picture and your path toward attaining the goals you and your client have set. Recognize and dismiss nit picking, or escalating minutiae to centre stage, for what it is. If drafting of a document is needed, make sure you are the one to do it because you will gain a better understanding of the matters in issue.

And lastly I think one must be constantly vigilant to avoid any conflict of interest. This is very dangerous for all concerned. It’s a sure fire way to lose clients and a damage a career simultaneously if the parties later fall out. It may look smooth, doable and “just this once” sensible, but don’t be tempted.”

– What are your survival strategies for dealing effectively with stress at the varying career stages?

Sir Peter:

Learn to say NO. And mean it.

“The life of every lawyer can be stressful and dependent on what you decide to do within the law the pressures can be very great. If you want a career as a leader in the profession, understand there will be periods of intense stress. Like all things, it’s how you deal with it that counts.

“The life of every lawyer can be stressful and dependent on what you decide to do within the law the pressures can be very great. If you want a career as a leader in the profession, understand there will be periods of intense stress. Like all things, it’s how you deal with it that counts.

What has worked for me is being as organized as I can be. I tried to work on the toughest tasks first. Putting them off increases the anxiety and pressure. When you deal with the difficult first, systematically and carefully, you can focus more clearly, without the clutter of unnecessary emotion generated by the thought you still not have tackled the hard ones.

I have always scheduled myself regular breaks regardless of how busy my diary said I was. I knew I couldn’t afford to become a work-aholic as that would have been a swift route to a loss of perspective, health, friends and family – everything I hold dear – everything that makes life worthwhile. I’d seen that happen and knew that balance was vital.

Realize you need to socialize, to laugh, and to share. Do not allow yourself to bottle feelings. That can lead to damaging yourself and others.

Accept and work within your field of interest and expertise. Do not be tempted by matters that fall outside those parameters despite how lucrative or important they appear to be.

Learn to say NO. And mean it. Weigh up responsibly what you can actively do to the standard you expect of yourself. Shift anything more than that on to others in the firm to deal with if they have the capacity to handle it. Do not be afraid to turn away work completely if it is beyond the competence of the firm.”

Legal issues

– What do you think are top current legal issues, and why?

Sir Peter:

“My major concern is affordability. Justice in civil cases is too expensive and becoming even more so.

The problem may be inherent in the system itself. Discovery and fact finding have been bloated by the proliferation of electronic technology. The volume of admissible data has hugely increased the length and complexity of cases. We now have to deal with emails, texts, and so on. In addition, documents produced by computer tend to be much longer.

Our already complex trial system becomes increasingly more so. Briefs of evidence and cross examinations get more and more detailed. What was already long is now getting longer.

And yet, longer litigation, whether in the courtroom or in arbitration, needs to be paid for.

The adversarial system may not be the best way of dealing with modern litigation.

I have no solutions to offer, but I sincerely hope we find an answer soon.

I say this even though I do appreciate that the problem has been addressed at least partially through the new discovery rules and some streamlining of the processes in the Appeal Courts. The use of written submissions there has pulled back the length of hearing time spent on each case.

Another concern I have is that as a society, we collectively expect too much of the legal system. We have become more “me” conscious – carrying a sense of entitlement that appears at times to overlook personal responsibility. Where once we shouldered mishaps and reversals of fortune stoically, we are now increasingly looking for someone to blame, and for someone to compensate us.

…we run the risk of our justice system being hijacked and consumed by self-serving trivial and ultimately indulgent cases

The result is that we run the risk of our justice system being hijacked and consumed by self-serving trivial and ultimately indulgent cases brought by people who can afford to pursue their goal: a public affirmation of rightness.

New legal issues tend to arise around the bedding in of new legislation and that requires interpretation. A recent example has been the substantial case law on the (very successful) new Evidence Act. And there will surely be legal – and moral – issues to be grappled with as a result of new technologies, such as genetic engineering – which is simply not going to go away as some would like.

Technological advances in many fields have long eclipsed what was thought possible or even imagined ten or twenty years ago. Privacy, genetics, medical, environmental – are all areas where the law is increasingly challenged. Our understanding of what is right and good, either for us collectively or individually, is being challenged as never before. At least, there is no danger of boredom for lawyers confronting the challenges.”

Who would you like to see interviewed?

You are welcome to forward the names of people whom you think fit the title legal luminary. Please send your suggestions through the response form below. We look forward to hearing from you.